Sustainability, Spirituality, and the Solar System

2. The Advent of the Cosmic Christ and the Loss of the Sacred Canopy

For the early Christians the birth of Jesus of Nazareth was not just an event in human history. They believed that Jesus was a unique human being sent by God from heaven whose coming presaged a new age for humanity and the cosmos. But there was no consensus as to the time of year when Jesus was born. And since birthday commemorations were a pagan practice, the earliest Christians did not commemorate the birth of Christ in an annual festival.

Mapping the Birth of Christ onto the Solstice

As the Christian church spread through the Roman Empire from the first Christian century, theologians sought to establish a chronology of Christian history from the birth of Christ onwards. In his Chronographiae (221) Julius Africanus wrote that Jesus had been conceived by his mother Mary on March 25. The date of March put the conception of Jesus around the time of the spring Equinox in the Northern Hemisphere.

The conception of Jesus is referenced in the Gospel of Luke 1. 26-38 in an episode known as the ‘Annunciation’ in which the Angel Gabriel appears to Mary. She is told her she is to bear a child who is to be called Jesus (Jeshua in Aramaic) and that he will inherit the throne of King David and his kingdom ‘shall have no end’. Leonardo da Vinci’s visionary Renaissance depiction of this scene sets it in Northern Italy and depicts the angel having just alighted in front of Mary.

Shortly after Julius, Cyprian set the date of the conception of Christ as March 28. In so doing he associated the birth of Christ with the birth of the Sun in the Roman calendar according to which the world was created on March 25 and the sun on March 28: ‘O! The splendid and divine Providence of the Lord, that on that day, even at the very day, on which the Sun was made, Christ should be born.’ The Romans worshipped the sun, or Sol, as a deity. In associating Christ with the sun, Cyprian took a crucial step in replacing the worship of the sun with Jesus Christ in the Roman world.

But it is not until two centuries later that we find the first record of the Nativity (later named Christmas) being celebrated, in Alexandria, on December 25, AD 432, when Paul, Bishop of Emesa, preached before Cyril on Mary as Mother of God. The subsequent Julian reform of the Roman calendar recognised December 25 as the winter solstice, and March 25 as the vernal equinox thus underlining the Western Roman identification of these dates with the conception and birth of Christ.

In the Eastern Church, which flourished in the Eastern half of the Roman empire (Byzantium), the Nativity of Christ is celebrated on the same day as Western Christians began to celebrate the visit of the ‘Magi’ to the infant Christ in Bethlehem, twelve days after the birth of Jesus, on January 6, in the festival known as the Epiphany.

Easter, the Vernal Equinox, and the Moon

The dates of the celebration of the death and resurrection of Christ, and hence the dates of the annual six week Christian fast of ‘Lent’ in preparation for ‘Holy Week’, were determined in the West at the Council of Nicaea in 435. It was decided that the resurrection of Christ would be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon of the vernal equinox. The vernal equinox is the date when days become longer than nights in the Northern Hemisphere and heralds the end of winter and the coming of spring.

The Venerable Bede lived in the seventh century AD in a Benedictine monastery in Monkwearmouth in the English kingdom of Northumbria. Bede had extensive knowledge of astronomy and was the first Western Christian to attempt accurately to chart the phases of the moon in the Julian calendar established by Julius Caesar. In The Reckoning of Time (703), Bede notes that the month of April, in which Easter often fell, was the month in which the Germanic goddess of spring, Eostre, was celebrated. Rather than ban the cult, the English monks in Northumbria decided to overlay the name and symbolism of the old English and German Springime celebration onto the celebration of the Resurrection subsequently known as Easter.

The mapping of the Christian ritual year onto astronomical events reflects the interplay between Christianity and the pre-Christian cults of Greece, Rome, and the Germanic kingdoms of Northern Europe. And the central place of the solstices and equinoxes in the commemoration of the key events in the life of Christ integrated Christian beliefs into the ancient, and globally dispersed, traditions of astronomical and astrological knowledge, as well as into the natural rhythms of the cosmos in the Northern hemisphere.

Christ as Microcosm to the Macrocosm

Saint Paul of Tarsus was the first to develop a theology of Jesus Christ as a ‘cosmic’ divine being. In a famous passage Paul says that the Son of God is the ‘image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation’ who mediates between the visible and invisible, heaven and earth, in whom ‘all things were created’ and in whom ‘all things hold together’ (Colossians 1.15-20). Theologians Irenaeus of Lyons, and Maximus the Confessor, developed Paul’s idea of the cosmic Christ. They described Jesus Christ as the divine microcosm in which the universe - the macrocosm - originated, holds together, and is being renewed.

Belief in the microcosm-macrocosm relationship is found in many philosophical traditions from the Indian Upanishads to the German romantics Schelling and Novalis. It declined in modern Western culture with the rise of modern natural science. But it is still to be found in minority contemporary traditions and practices, such as Rudolf Steiner’s ideas about biodynamic/organic farming, and in ‘New Age’ thought. In the Abrahamic faiths its influence remains strongest in contemporary Eastern Orthodox Christianity, and in Islam. Its influence endures in stone throughout Western Europe in the great cathedrals of medieval gothic, and in the gothic revival buildings of the nineteenth century.

It is was in the writings of the neoplatonist Plotinus that the microcosm-macrocosm relationship was first fully articulated in Western philosophy. For Plotinus, every human person - and even the organs of the human body including the brain, heart and liver - correspond to aspects and objects in the material cosmos including the sun, moon, planets and stars. In this metaphysical perspective, the order humans experience in their bodies and minds, and in the Earth, corresponds to a transcendent order in the visible heavens and beyond in invisible realms accessed by divine revelation, dreams, and visions.

The microcosm-macrocosm relationship is a crucial influence in Christian sacred architecture. The sixth to ninth century mosaics of Ravenna in Italy are among the most extensive visual records of the tradition in Western Europe:

The microcosm-macrocosm tradition was revived in European art and philosophy at the Renaissance: as for example in Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing of Vituvian man, and in the Cambridge platonists such as Robert Fludd:

In the Muslim world the microcosm-macrocosm philosophy continues to inspire the building of exceptional structures, such as the Grand Mosque in Oman, completed in 1998:

Modern Astronomy and the Loss of the Sacred Cosmos

The birth of modern astronomy occurred with the development of high quality optical glass in the late medieval ages. These led to the telescopes used by Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton and their heirs. Their observations led to the modern scientific rediscovery of astronomy. This revival was strenuously resisted by the Roman Catholic church which had lost the microcosm-macrocosm philosophy that endured in the Christian East and the Islamic world, as well as in Asian religions. Consequently in the West, modern astronomy, and modern science more broadly, took increasingly materialistic and reductionist paths. So much so that by the twentieth century the existentialists whom I read at school, such as Jean Paul Sartre, would lookup to the heavens from Earth and declare that they are empty of being, and of meaning.

Sociologist of religion Peter Berger coined the phrase ‘sacred canopy’ to describe the traditional pre-modern significance of sacred cosmology - belief in correspondence between heaven and earth - and the huge psychological and social significance of its loss in Western industrial societies:

Many blame the contemporary ecological crisis on ‘materialism’ and ‘consumerism’. But as Seyyed Hossein Nasr first argued, at the root of the alienation between modern industrially-contructed lifestyles, and the wreckage these make of the larger than human world, is the spiritual alienation between modern Westerners and the universe:

For many moderns there is no heaven in the sense of a realm whence their souls came, and to which their ancestors have returned. When they look at the heavens they merely see lights in the sky; they don’t have a sense any more of a spiritual connection between their life on Earth and the realms - visible and invisible - beyond the sky.

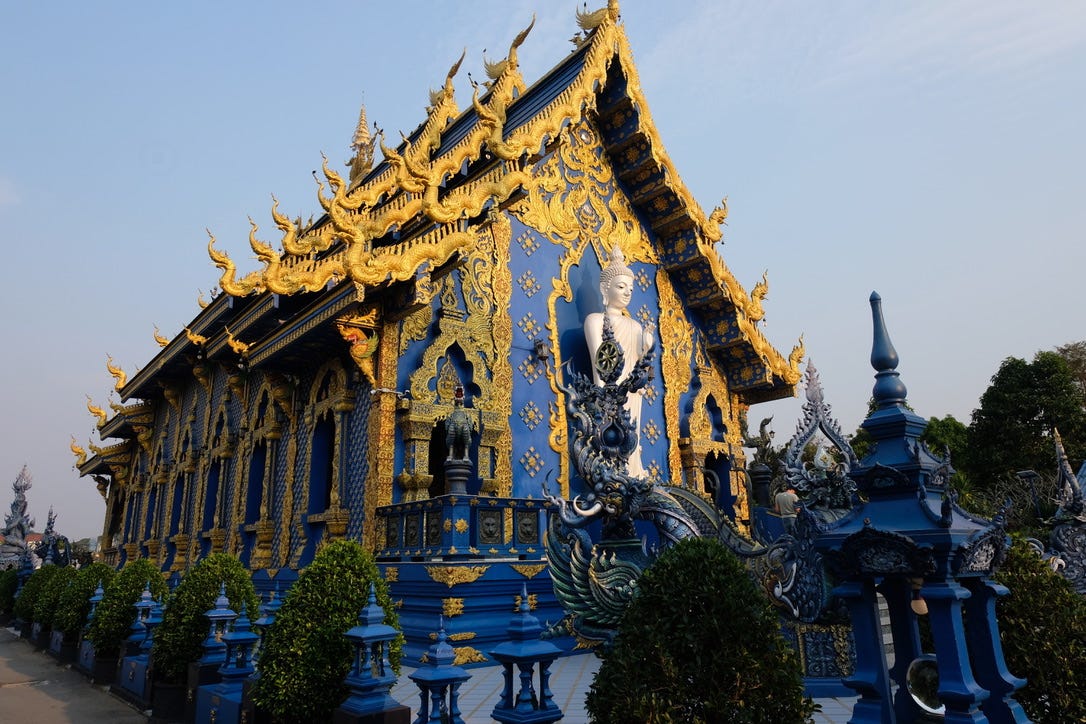

All premodern people believed that their destinies and that of the heavens were spiritually and materially connected. In Southeast Asia such connections are widely displayed: in the comet-shaped figures that adorn Temple roofs in Thailand, in the seven grass-roofed structures of Balinese temple towers, and in the new moon symbol that sits atop Javanese mosques. This belief also informs ancient astronomy, and the megalithic structures, such as Gunung Padang in East Java, and Angkor Wat in Cambodia, which, like the recently discovered Gobekli Tepe, show astronomical knowledge of the changing positions of star systems in the skies over millennia as a result of small changes in the Earth’s orbit that shifts the view of the skies, and which astronomers now call precession.

Ancient belief that human destiny was literally made in the sky was not however just a spiritual belief. There are thousands of archaeological depictions, and mythical traditions, that indicate that the ancients experienced sudden floods, droughts, and other rapid climate events and that could wreak inter-generational devastation. But almost universally, archaeological and textual records indicate that these events often occurred rapidly, as a result of changes in, or objects from, the heavens and not from Earthly processes.

That the history of life on Earth has been regularly punctuated by catastrophe, and that these catastrophes mainly came from the sky, helps to explain the apparent obsession with the heavens, and the surprising ‘archaeoastronomical’ knowledge, of our pre—Copernican forbears. As I observed in my last post, from the nineteenth century, catastrophism was displaced by the gradualist view that life evolved slowly over millions of Earth years and punctuations in its history are mainly terrestrial in origin. In this new perspective the appearance of the land, sea and sky today, and the climate and weather that humans and other animals currently experience, are products of almost exclusively gradual evolutionary processes.

In my next post (I intend these to be once a week going forward!) I will explore the way in which the modern Western ideational shifts from sacred cosmology to industrial materialism, and from catastrophism to gradualism, are mirrored and replicated in contemporary climate science. Against ancient and modern astronomical theories of climate change, many academic scientists and governmental agencies now hold that contemporary changes in the Earth’s climate are exclusively terrestrial, even anthropogenic, in origin. This novel view has been adopted by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panels on Climate Change, and by most national governments and private companies. Instead of a sacred canopy, these agencies intend to control and direct all human agencies on Earth via a vast technocratic canopy, topped by thousands of near earth satellites that will increasingly obscure the night sky, and which are said to be needed to control ‘carbon emissions’ to stop the Earth’s climate from changing.

I breathed out carbon while writing this. The jungle ravine next my house in Bali absorbs carbon, turning it back into oxygen with the sun’s energy via photosynthesis. To be anti-carbon is to be anti-life, and to view humanity as irredeemably alienated from the solar system.

There is something deep at issue in the modern industrial ideology of ‘climate change’, that for too long, as a progressive academic ‘environmentalist’, I replicated in what the late Bruno Latour called my ‘carbon theology’. The ideological veil of the novel industrial theory of climate change mystifies the extensive empirical evidence - from within the Earth’s magnetically charged core and the volcanic vents of the mantle, from the cosmic rays and coronal mass ejections of the sun, and from the comets and stars - that humans in our long history have experienced catastrophes from the heavens in the past, and that we may do so again.

I recognize that sunset. Excellent theological work, Professor. And, if I may share with you my treatment on Issa. - Your friendly neighbour... https://chronos.substack.com/p/issa-i

This is beautiful Michael ! all very important stuff.